(June 2 is International Sex Workers’ Day. This is a prize winning story revolving around the adventures spanning an evening of Donna aka Devi, a fictitious streetwalker based out of the Thampanoor in Trivandrum, Kerala. Dedicated to all Donnas and Devis out there. May your profession be legalised and organised so that you can live with dignity and courage.)

Two things struck him when he slapped her hard across her face:

- unlike in the movies his hand didn’t swing in a semi arc, but stopped right on contact and,

- again unlike in the movies, it sounded like a dull thud and not as if a cracker burst.

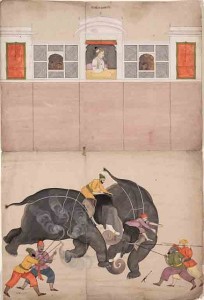

His hand stung too – probably not like in the, well, fuck it – and he winced. She saw him redden in pain and very quickly – but not quick enough – she lowered her gaze with a defiant meekness. The pain – and the fact that she saw him in agony – only served to aggravate his anger. He kept up the violence mostly to save his face. With his left hand he mangled her cheeks and pulled at her nose as if trying to pry it off her face; some zits on her nostril broke from his nails and bled. Probably the sight of blood or just plain exhaustion, he sat on the bed panting. She stood unmoving. He was still shivering with rage and tried to kick her but his legs didn’t make contact. She moved a few steps backwards maybe to get a better look at him. He was perspiring hard: beads of sweat amassed on his forehead before flowing in minor tributaries over his temples to his shirtless torso, trickled down his nipples, traced a busy path over his bloated up belly like crystal termites on a pheromone trail before getting sucked in by the elastic band of a faded Tantex underwear. His right hand swung at her wildly, his fury refusing to ebb. She looked up at him more in amusement than in disbelief – was he so brain dead to see that she could pulverise him if she wanted to? Physically she was stronger, much stronger, than the pensioner who sat shuddering from head to toe on the bed. He swung out at her again, but his limbs were listless now like the flailing wings of a dying pigeon in the peak of summer. His face tilted to one side and his lips opened and froze midway like someone having second thoughts about what he was going to say. Slowly he slanted over the side of the bed, staring at her through glazed eyes. The pensioner, Venu, who had retired from the public works department as a chief engineer some years ago, was a severely diabetic man and he had just embarked on his second stroke which would soon prove fatal. But Devi who was with him, the one at the receiving end of his tragic little rage a little earlier, was clueless. After all, hookers do not ask for the medical history of customers. So screaming or calling for help were the last things that came to her mind. Even if it did occur to her – to help him, if at all – she was soon relieved of such noble urges.

Venu and his other pensioner friends had gathered at the Rajadhani Bar in East Fort after collecting their pensions from the different sub treasuries spread all over the city; most of them came by auto rickshaws from Vellayambalam and Vanchiyoor and one even from Kazhakkoottam, 15 km away. None of them wanted to miss these monthly get-togethers when they swam in parotta and chilly beef or Malabari chicken curry and bottles of Honey Bee brandy away from the watchful eyes of their wives; most of them had medical histories which they wrote over the 30 plus years sitting behind desks doing civil service. The rest of the month they acquiesced to salt-less curries and sugar-free coffees; wheat porridge and other baked suds even when the wives themselves wished at times they’d object for that occasional eat out at the Indian Coffee House. The few hundred rupees missing from the pension was attributed to the ‘employee welfare fund’ which actually never went above ten or fifteen rupees. But most of the women being housewives had no means to crosscheck. Venu had to account for more – 1500 rupees, to be exact. The last month and the month before he had told his wife that George, an ex-colleague, who retired as assistant engineer, was borrowing the money from him. He had even cooked up a tale on how his wife was sick and was admitted at the KIMS Hospital. So the nights he spent with hookers in lodges in Thampanoor were thus spent with George, consoling him, giving him strength. Anyway it was not like they needed the money or anything. Their kids were grown up and comfortably settled – the boy was with Wipro in Bangalore and the girl was married to a pharmacist in Canada. Still Venu made it a point to explain the missing monies as soon as he reached home so that his wife didn’t ask him unawares.

After the party they all came by auto rickshaws to Thampanoor bus terminal and parted ways promising to meet a month later; George wouldn’t be making it as he was going to Riyadh where his daughter just had a baby. Venu made a mental note of not uttering a word of George’s foreign trip to his wife.

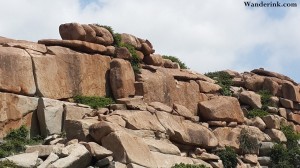

It was only early dusk and the nocturnal crowd would take a while to appear. Venu looked at the spiral Indian Coffee House with lozenges of light coming out of its numerous jaalis and on a whim he walked towards it. Probably the thought of all the dietary constraints that awaited him he wolfed down a plate of meat cutlets with the limp onion salad that always accompanied it. Exiting the red brickwork landmark that looked like a hammered-down Pisa tower he walked towards a roadside vendor and bought a Gold Flake king size cigarette. Fifteen fucking rupees: he knew he was paying for the beat cop too.

![5]()

He walked back to the bus terminal, the new bus terminal, around which everyone was still figuring their way. The only thing they all knew for sure was that buses were not to be chased like in the olden days – dissuaded by a gap on the approach with smooth steel rollers placed wide enough for the running limb to slip through. Even then most still kept at it – gingerly tiptoeing over the rollers only to find the bus has disappeared inside the terminus. Right on cue the guards would come out and chase them back over the rollers and this time some would actually slip and smash their testicles or lose their sandals into the cavernous hollow below. Venu watched the tamasha for some time and walked towards the entrance proper. He walked with not very steady steps along a slanting walkway to the entrance atop a flight of stairs. Shops – spaces, actually, denoted by downed shutters – extended to both sides of the terminus all along the ground, first and second floors. A few on the first floor were already taken, while most on the ground floor remained shut probably being more expensive. The only spaces on the ground that were occupied were the pay and use toilets, at both ends of the wing; all the spice ensuring good business. There were stairways going up and down and large areas cordoned off with yellow tapes probably earmarked for escalators. It was deserted save for a pilgrim or traveller who had spread out his mundu to dry after washing it while showering in the pay and use toilet. As soon as it got dark and the shops shut, it’d be a stopover for streetwalkers to lure customers and gays looking for companions – with darting eyes and tongues respectively. The pilgrims got quick blow jobs while their mundu dried for ten or twenty rupees. The security guard, who bastinadoed his way across the rubble and balustrade at regular intervals, turned a blind eye to the shenanigans. Unless he spotted someone ripworthy, that is – the clients, usually.

Devi was squatting on the landing of the stairway when Venu met her; they had signalled each other with their eyes and finally Venu followed Devi up the steps to a dark corner where a scaffolding stood. Some rags had been spread between the frames and there were blotches of paint everywhere. Devi went under the crossbrace in one fluid motion while Venu stood on the other side, outside.

“Quickly,” she said tugging at him by the belt.

“How much?” he asked shuffling away from her grasp.

“Two hundred, in the mouth,” Devi said. Later when the customer was caught in the throe-shold, she’d add a hundred rupees more if he wanted to come in the mouth. It always worked; tested trick of the trade.

“No, wait,” Venu said, now moving well beyond her reach.

“Fine, one hundred then, but by hand only,” she said impatiently. Business was pretty low; she hadn’t made much money the whole week. Some said it was the case in every business – heavy discounts were the norm.

“No, not that, not like that,” Venu said and asked “how much for the whole night?”

“One thousand rupees.”

Venu looked at her, seeing her for the first time. Though she sat on her haunches in front of him he could see that she was a big woman with long, muscular hands. She emerged from beneath the scaffolding like a sinewy big cat, a head taller than him with glistening dark skin. Her well-oiled hair was braided and reached all the way below her knees – one reason he didn’t bargain when she quoted her price. He always had a fascination for well-rounded women with long hair – a sort of conditioning by the leading heroines of Malayalam cinema during his youth like Sheela and Srividya. In fact he kept breaking step so he could take a look at her long braids as they headed to the lodge.

He had hardly mounted her a while later and he ejaculated.

“You’re a real devi,” he said probably by way of explaining.

“My real name is Donna,” she replied. “I just stick to Devi as it’s easy.”

“You’re still a devi,” he said. “Lovely long hair and big rounded breasts and…and…you even have more muscles than me. Were you into sports?”

Devi/Donna was a fisherwoman from the nearby port town Vizhinjam. Her husband Andros owned a fishing vessel and brought back a decent catch on most days. That was a long time ago. A diminishing catch over the years due to climate changes coupled with being an incurable soak saw to it that the boat had to be sold off. But he’d still go in other boats on a daily wage basis and she began to hawk fish for other contractors in and around Vizhinjam town. On most days she had to walk till Mulloor from Vizhinjam before she sold off her stock – three kilometres under the harsh sun with the steel vessel balanced on her head. When the announcement for the new port was made along with the promise of jobs for some 20,000 fishermen who’d lose their livelihoods, Andros stopped going to work altogether. It didn’t really occur to him that technically it was not the port which was claiming his livelihood.

It became difficult for Donna to support the family through fish mongering. But prostitution was still not her first recourse: it was stealing. She would ride in the buses that plied between Vizhinjam or the touristy Kovalam nearby and Thampanoor and steal off the rucksacks of backpackers or pick the pockets of enamoured domestic male tourists who’d press themselves up against her. She would return the pressure with a squeeze here and there and sometimes through the pocket. The picking went down with the quality of tourists visiting Kovalam. Even the phone and other accessories she flicked from the bags were cheap Chinese.

“There’s nothing in that big, stringy bag, I tell you,” she said.

“Most of those who come to our country are the hairdressers and butchers,” Venu replied trying to cover up his worry over a still-deflated member with his grasp of tourism demographics. He rose from the bed to go to the bathroom. Whatever little action had left him a little dizzy and he didn’t want the hooker to see. He hoped it’d be the Honey Bee but he wasn’t sure. Flashes of a fateful protest march years ago when he suffered his first stroke and had fainted floated across his eyes; his colleagues wrapped him immediately in a red flag and shouted slogans of martyrdom – albeit prematurely. He tried to wash them away by splashing water over his face. He was standing clutching the rim of the basin when her words struck him: hands through the pocket. Probably the bathroom door didn’t have a latch or maybe Devi/Donna was expecting the sound of the flush to announce his imminent exit. Whatever, when Venu emerged from the toilet he found her rummaging through his shirt pocket, on the verge of discovering the secret pocket sewn on the inside where he carried the serious dosh.

The stoic indifference Devi/Donna maintained throughout the assault didn’t mean that the slaps didn’t hurt. There were angry welts across her face and blood from the broken zits from the later mauling – these though had started to itch now. After watching Venu convulsing for some time, it did occur to her that it could be a seizure. Before her marriage to Andros she had a boyfriend Boney who worked as a tourist guide cum porter cum drug peddler cum call boy out of Kovalam. Boney was now running a small but successful awning business in Kyoto after marrying a 65 year old Japanese divorcee whom he accompanied to Agra where, during a midnight viewing of the Taj Mahal, he fed his well-practised spiel of Indian men and everlasting love. Bodh Gaya and Boney’s own adherence to right speech and action, the visa was made.

Boney had on many occasions acted out for Donna the paroxysmal motions of a 70-year old English tourist, a paedophile, high on the hash Boney had sold him hit by a stroke while trying out some gymnastic antics with a boy, who again, Boney had brought. Boney was in the same room rolling joints for his wife when it happened. In the supreme compassion and erudition that comes your way only when you are stoned, Boney and the English lady first decided to let the boy out and then wait till the guy had calmed down a bit before calling room service. The room service called the manager who alerted the hotel doctor who proclaimed the tourist dead on (the doctor’s) arrival. More than mimicking a Mammootty or Mohanlal, this was Boney’s favourite – he used to enact the grotesque fish-lip and gurgle, the flailing-arms-going-rigid routine with panache – after sex, while sharing a joint, while making up, right till Donna announced her wedding to Andros. See, one doesn’t marry boys like Boney. They are too funny for life.

Venu now lay on the bed and moved spasmodically, with a rigidity unlike before. Devi hastily put on the underskirt – she wasn’t wearing panties – and draped the sari hurriedly around her. She pulled on her blouse – she wasn’t wearing a bra – and hooked it into place. Just as she was about to reach out for the shirt again and its little secret pocket with the money, the door burst open and two guys stood in front of her: one was the night manager and the other the youngster who showed them into the room when they checked in.

“Do you want to be arrested for this man’s death?” It was the manager, in a curiously calm voice.

Devi knew better than to argue and turned around to leave. Probably hoping for a last moment change of heart in the guys she turned back to look at them as she reached the door; after all she was the one responsible for their good luck. One had already begun relieving the secret pocket of its contents while the other was switching off the mobile phone found in the trouser pocket. They looked up at her, menace gradually clouded their eyes.

“We’ll not tell you again.” The room boy hissed. She flew.

She got it that they had been peering through either the keyhole or some other crack or crevice in the mirror or the wall all the while. She also knew that the pensioner would be found in some trash heap the next day and photographs would be stuck on ‘request to identify’ ads in papers which wouldn’t tally with the sprightly ones on the ‘missing’ boards in police stations. She also knew that she actually ought to be thankful to those guys – what if they denied her what was fairly hers? She had never been to a police station and though she knew they didn’t shave off hookers’ heads any more, she was still scared. Besides her husband and neighbours would be notified of what she had been up to; not that they didn’t know nor cared but an official opprobrium would mean approbation to harassment and innuendos she was subject to with an increasing frequency these days. She was just another hooker trying to eke out a living. Hopefully it would all be over once the new port opened. For her and others like her living around the multi crore project area.

***

Devi went back to the bus terminal where the lathi-ed security guard let out a loud cough as she passed. It was just his subtle way of letting her know that he knew and she should also know cuts were in order. She met his eyes fleetingly to let him know that it was forthcoming.

Patience.

She went straight to her corner; the day, the week had been bad and she had to at least make a hundred rupees before she took the last bus to Vizhinjam which was in another two hours. There instead of the usual mundu-drying pilgrim resting half naked listening to religious songs on the mobile phone sat a blond-haired German, Wolfgang, in cut-offs and wrinkled tee shirt and smoking a wrinkled cigarette.

![6]()

Wolfgang was waiting for the 10 PM Sulthan Bathery bus to take him to Calicut; he would be reaching at 6 in the morning. His wife Catherine had already reached from Kochi. Besides an insurance underwriter he was also a travel blogger with a decent number of RSS subscriptions. As he wanted to cover Kovalam for his readers so while his wife headed to Calicut he bussed down to Trivandrum and Kovalam just for a day.

He was keying in on his Acer Aspire when she sidled towards him:

The most fun you will have in Kovalam is body surfing, be prepared to be roasted alive though it’s not yet Thanksgiving…

He kept typing, giving her just a cursory glance:

The acid is missing from the beaches but the beer server assured me it is available, has to be, there is reggae all over and every second tee shirt has Bob Marley on it…

He then asked her without looking up:

“You know I’m from Berlin, the land of King George Brothel?”

She looked back at him quizzically.

“You know, fuck-all-you-can?” He took a deep drag and flicked the cigarette away before looking at her and smiling.

“Fuck, yes, fuck.” She replied making a gyrating motion with her hips.

“No I can’t you see, I have a bus to catch,” he told her. “Besides I don’t think I will be able to get it up, you see am all stoned.” He spread out his long fingers which drooped down like limp members after an orgy.

“Come, we fuck, yes.” Devi repeated.

“Well, I guess that will be a new one to tell my readers then,” he said.

And wrote:

But what definitely is available is love…free love…they come to you…out of the blue. Or dark. Dark…

“But lady I must tell you that all I have is about an hour, I will have to leave soon,” Wolfgang told her before setting off towards the Aristo Junction with its many hotels. None of them were ready to give room by the hour, however one seedy one finally agreed on the condition that Wolfgang gave it a five-star rating on TripAdvisor.

Beneath the rickety fan Wolfgang’s golden mane flew. Each time he thrust into her she gasped – pain and pleasure in equal parts. ‘The blacks have the biggest dicks,’ Boney had once told her as they were about to watch a porn movie at a friend’s place. ‘It will just tear you apart.’ ‘Thank god you are not a black,’ she had replied to which everyone had laughed, including Boney. For whatever it was worth Boney was a good sport. She missed Boney.

“I love it, I love it,” she moaned remembering the lines from the movie years ago. “Faster, faster.” She didn’t remember the rest: harder.

She clutched and clawed his buttocks and cupped his testicles – did everything she knew to make him ejaculate fast, nothing worked. Finally after about half an hour Wolfgang crumpled on top of her with a loud scream. Devi was too tired and sore by then to do anything: she lay motionless feeling the still-spurting semen inside her.

Wolfgang sat up and dressed. He rummaged in his rucksack and fished out another crumpled joint which he straightened out and lit. After taking a few drags, he offered it to her. She pulled a little; she was never into drugs though it was available aplenty with Boney.

“You smoke hashish,” she said.

Wolfgang wasn’t sure whether it was a question or a statement. He just smiled at her and nodded.

“You are, how do I put it…a good time woman?” He asked leaning back on the bed. Enlightenment had its many sources.

“No…no…no,” she replied. “I student, I fuck for fee.” Boney had told her it worked every time with the Europeans – saying you were a travel guide or a hooker because you had to finance your way through university.

“Oh you have a fee? You mean you are a…prostitute?” Wolfgang seemed mildly surprised at the possibility.

“Yes fee…fuck…fee.”

“How much?”

“Only ten thousand rupees.” Most Europeans are nice and some are dumb too – if Boney was to be believed. And this one was stoned to boot.

“What the fuck!” Wolfgang sprang up from where he sat like the cushion bit him, spat out what remained of the joint from his mouth. “Did you say ten-ficking-thousand rupees? Call the bloody manager!”

He banged his fist on the wall and dragged his rucksack off the side table before opening the door. True to reputation or prompt service, the manager stood right outside the door straightening up as if he had just finished tying up his shoelaces.

“Hey you,” Wolfgang screamed at him. “This, this whore is asking for too much money.”

“How much, sir?” The manager asked deferentially.

“Ten-fucking-thousand rupees.”

“How much did you ask him for?” The manager asked Devi in Malayalam.

“Ten thousand,” she replied.

At this the manager laughed out loudly which further irritated Wolfgang.

“Hey, sorry, I cannot participate in your joke,” Wolfgang barked at the manager. “I have a bus to catch.” And he was off. The last thing Devi saw of Wolfgang was a hazy yellow glint reflecting off his open mane as he huffed down the hallway.

“Look at them,” the manager told Devi turning to follow her gaze, “which part of them makes you think they have that kind of money?”

As Devi walked away she heard the manager mutter “I just hope the scoundrel gives me a good review on TripAdvisor.”

‘Must be some new magazine,’ she thought as she headed back to the bus terminal. ‘If Boney was around I could’ve asked him.’

***

Fr. George spread out his white towel to dry over the balustrade and looked closely at his watch. It was dark and he couldn’t see the time, he tried twisting his wrist in different directions to get a better look.

“It’s almost 10,” a female voice said.

Fr. George looked in the direction of the sound – it was just a few steps away from where he stood.

“Oh, I’m so sorry, I didn’t see you,” he said as if he had walked into somebody’s bedroom by mistake. There was no reply.

“See I’m coming from Adoor and somebody who sat in the front seat threw up soiling my towel, but thankfully the rest of me was saved,” he said and guffawed. “By god’s grace.”

“Are you a priest?” The female voice asked.

“Yes,” Fr. George answered. “I’m on my way to Patna, there’s a train at 12:50 AM.”

“What do you do in Patna?” She asked.

“Oh I teach in a school, actually I am the principal.”

“So what are you doing in Kerala?”

“I came for the Onam celebrations. Actually I was the chief guest of a school here whose principal is my brother.”

“If I come to Patna with you will you help me find a job?”

“But what do you do here?”

“What do you think I’m doing here?” She asked, sitting up and moving closer towards the light. The pallu of her sari was spread out as a makeshift mattress and Devi was almost naked waist up. Fr. George swallowed hard before regaining his composure.

“We have a destitute home in Patna and I might be able to admit you there,” he said.

“To hell with your destitute home, I have a family to feed.”

“But what work can you do?”

“I can fuck hard – you can fuck me all you want. And your father superior too.”

“Child, remember you are talking to a priest,” Fr. George rebuked her gently.

“Why, you guys don’t have the dicky?” By then Devi had given up all hopes of landing a customer or going home. Her last bus would be leaving soon and the nearest male was a priest with a train to catch.

“As a matter of fact we do,” Fr. George said. “We’re also humans, you see.”

“Then prove it!”

“What’s your name, kid?”

“Devi, er, Donna.”

“Devi or Donna?”

“My real name is Donna and I use the name Devi, for, er professional reasons.”

“Christian?”

“Yes, Latin,” she said. “And I’m tired and now be the famous Good Samaritan and give me just sixteen rupees to go home,” she wanted to add, but didn’t. Actually.

“What are your rates my child?” He asked. “I hope you won’t fleece me, I’m a poor priest, you know.”

Just as they were heading up to the first floor, now completely shrouded in darkness, the security guard came thud-thudding the floor with his lathi.

“Where do you think you’re going?” He asked. Loud enough for the priest and the prostitute to sink in their steps but not loud enough to attract the attention of those passing by.

Fr. George took out a hundred rupee note from his pocket and handed it to the guard who pocketed it and walked away, thud-thudding after him.

‘Poor priest, bah!’ Donna thought, sure that there was more where it came from and began to run through her mind the usual tricks of additional extrication. He looked like a good sort and probably she should stick to being nice and give him a fair deal. Beginning with a good time.

“Am I your first customer today?” Fr. George asked as they neared the scaffolding.

“No, not at all,” she replied.

“How many before me?”

“There was a pensioner who paid two thousand rupees and then a German tourist who paid five thousand rupees.” She couldn’t stop the barrage of lies that scrambled out on their own. Force of habit. She looked sideways at the priest unsure whether he bought it. But he seemed to be lost in a world of his own. Was he smiling?

“Tell me more about these two customers,” he said.

“They were both men, like you, what else?” She asked.

“Like what they looked like, what they did to you, for how long. The German must have been great fun. Tell me about him. Was he fair? How big was he?”

Donna knelt beneath the crossbrace and went under the scaffolding. She took off her sari and arranged it over the rags on the ground before she lay down over it.

“Tell me…tell me about him…and you…” Fr. George gasped, leaning with one hand over the crossbrace, the other caught in a flurry of motion.

Just when Wolfgang slumped over Donna’s broad belly Fr. George squirted semen all over the scaffolding spangling the white paint blotches. Donna lay there looking at the silhouette of the priest – no hand, no mouth, just words did it. This was a first. She knew about joy (joi) videos from Boney. Maybe this was a live joy.

“How much do you charge for..,” the priest was still breathless and the words came out in rasps, “…for pissing?”

“I think it is one rupee but the ‘pay and use’ is downstairs.” Boney took off with the Japanese lady before he could show Donna any fetish videos. Boney himself was a pretty straightforward guy.

She knew something was amiss, that she was missing something. She peered intently at the priest’s face but couldn’t make out much because of the dark. Still she could make out an ethereal calm as if he was in the midst of a séance. When the first few drops of the warm, acidic shower hit her she thought it was maybe the varnish from the plank on top of the scaffolding left behind by the labourers. Then some fell on her lips and the burning sensation singed her. She at first shrank violently away from it before lashing out. But there was not much room within the caged-in area for her to move; she thrashed about her hands, splattering some of the piss back at the priest.

“Stop it, stop it, you son of a bitch,” she hissed, spitting out what fell into her mouth. Above all the commotion she heard Fr. George grunting like a wild animal, his clenched teeth shone through the thickened darkness of the facial hair.

“I love it…I love it…” he groaned just as the piss tapered and dripped over. “You should…you should…kneel close and open your mouth.”

“You fucking sick animal…” she screamed headbutting him from beneath the scaffolding. Fr. George staggered and managed to regain his balance and not land on his back. In her hurry to jump over the crossbrace, she tripped over it and fell down with the whole scaffolding landing on top her with a plangent crash. It was not very loud because of the wooden planks on the top and the rags beneath.

The priest got up and ran without even bothering to zip up the fly of his trousers. He reached the ground floor of the bus terminal. The railway station was just across the road. But there was the security guy standing, leaning on his lathi, right by the entrance. Maybe he was standing there to ask for more money, the baksheesh due for the uninterrupted time. Or maybe not, he was just standing there, between rounds giving his lathi a break. Whatever, Fr. George decided not to take any chances. He turned around and walked hurriedly towards the bus entry – the one with the spaced out rollers. He heard some noises shouting behind him and he ran.

Those who heard the rending scream said it was preceded by a loud thud – almost like he was hit by a bus. But the security officer on duty vouched that no buses had passed when Fr. George slipped through the gap and hit his head. This was further corroborated by the station master who shook his head and asked, “Why would a learned man – a man of god – go that way?”

![]()