Life-altering journeys have less of an itinerary and more intent. To leave behind. To start anew. It is reminisced and written about as a spur-of-the-moment thingy which it is not really. But the apparent recklessness adds to the romance, gives it an edge. So be it. Anteceding it is usually years, if not decades, of unfulfilled living. It doesn’t always have to be one fraught with frustrations and disappointments but ironically could even have been one of material surfeit and sensory saturation. The long road beckons. Take it till the horizon and drop it all over the edge. And return like the rising sun. Sounds easy but the glory demands its mean pound of grit and grind. More so if you are a white collar worthy. And a mother. Much more if you are overweight. And carrying on with the boss.

As in-charge of the human resource department of an organisation till about a decade ago, Liz Earls sat behind a desk, a plump, almost-matronly figure, poring over appointment letters and employee training manuals. A divorcee with two teenage daughters, the only event in an otherwise non-happening life was the occasional clandestine tryst with her married boss – who inspired her to follow her dreams and who remains that special ‘one’ in her life. She gave up her job at the company and began to work as an erotic photographer – something she always wanted to do. Soon she began basking in all the attention from the men and women she was shooting and gladly gave in to their sexual overtures. She was hitting 40 and she knew there was a lot to make up for. She didn’t want to dwell into the past but asseverated to herself that she would make the most of every moment that lay ahead. Raffish dreams but they were hers anyway. And for her to take care of.

‘Days of the cougar: The outrageous visual diary of sexual adventurer Liz Earls’ chronicles her carnal voyage that lasted over two years across several countries. Her explicit sexual encounters with men aged 19 – 32 years, from all walks of life, shot either by herself, her companion or on timer, fill 250 glossy pages accompanied by inspired write ups. A coffee table book you may not exactly want to leave on the coffee table. “This is what I am, this is what I always wanted to do,” Liz makes no bones about her passion which has become a profession – her company Fantasy Capture in Los Angeles specialises in erotica and fetish photography.

Liz Earls, in a no-holds-barred chat with Wanderink.com.

‘Days of the Cougar’ made waves for the explicit sexual content. Understandably little has said about the years of travel that went into it. What was more liberating – the sex or the sojourn?

I think both are very liberating and they go hand in hand – it’s a bit like a package. Traveling opens you up to different cultures and meeting people that you wouldn’t otherwise meet. Travel has always been a part of my life from a very young age – so it comes very natural to me and I enjoy it very much.

Travel liberates, brings one close to different cultures, people. How else does travel work for you?

Travel reaffirms my spontaneity. For example, I had a New York trip booked, and then three days before the trip I got an invite to an erotic party in Paris. I booked a flight to Paris the day I was to leave for NY. And not only did I go to Paris, but I stopped over in Istanbul for three days, completely on a whim. Had an amazing time. I ended up missing the connection to Paris for the party and staying in Istanbul an extra day. It was quite an experience. I met a rug shop owner while walking down the street after a beautiful dinner and ended up dry humping him in the shop.

How much does the sex mean to you?

It really varies. I would say, 90 maybe 80 per cent of the time I only have sex for the art of it. Other times it can be like the rug guy – or the guy I met in a Sydney hotel elevator where we said almost nothing to each other. It was 2AM and I was wearing only a white furry Four Seasons bathrobe. He came into my suite and we fucked each other all morning. He left around 9AM and I never even asked his name.

What else do you look for other than sex when you travel?

I know I probably come across as a sex fiend but I really enjoy the scenery and culture and just generally getting to know a place. I look for models to shoot as well as new scenes to shoot myself in. I do want sex but it’s not all I want. I’m all about the experience, the journey, and if it happens to lead to sex, that’s cool, but I’m not an addict, I get plenty of it, so don’t feel the need to go after it, it just sort of comes to me.

Which all places have you been to, countries, in the course of your work?

(Laughs) Okay. Yes, I have been all over the world: Australia, Norway, Portugal, Spain, too many places to list quite honestly. I tend to travel continuously for a year, putting everything in storage, and going ‘nomadic,’ literally, just hopping on a plane and figuring it all out as I go along. I am leaving again this April and will be travelling for about eight months. I like to leave myself open because often times I will get an invite to a place I had not even considered on my radar like Poland or Columbia. I must have been around the world five times or so. There are still places I haven’t been to like many countries in Asia and Africa including India. It’s easier to list places I haven’t been to than the countries I have visited. There really isn’t a place I would not want to go. Every place is unique though unfortunately not all countries are safe to go to.

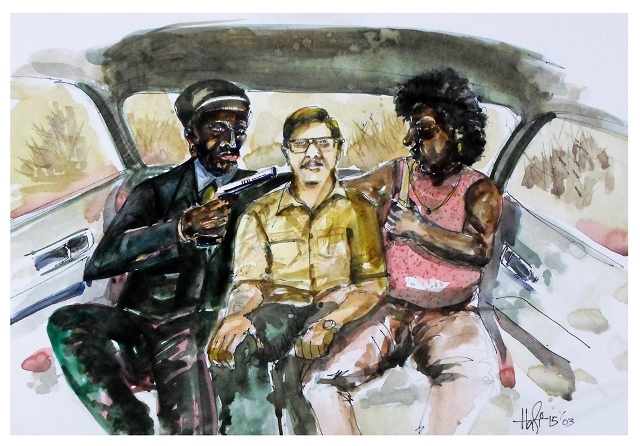

Has your sexual quest landed you in any potentially threatening situation?

No, I have been lucky, I suppose, but also I think I am very intuitive. There have been maybe two or three people at most that I wouldn’t want to see again. None of them dangerous, but they got too attached is more the issue. This one person, one of the three I wouldn’t see again, was an interesting situation. He came in and seemed super nervous, put money in a drawer for me, which is really unusual. It’s generally just, “Here you go for the photos.” We had an interesting session, not rough, but definitely edgy Afterwards, we ended up talking for over an hour, maybe two. It’s not unusual for sessions to become like therapy as I am genuinely interested in each person I am with, even if it’s just for a few hours. I could tell he felt close, and he hugged me for the longest time as he was leaving. He was genuinely moved, and I could tell he felt bad that he gave me counterfeit money. Yes, the money in the drawer wasn’t real. I knew it even before the session began, just a feeling. But something in me said to let it go. And I’m glad I did. It’s not always about money and I honestly know that that night changed him.

How do you turn down somebody you are not interested in without risking getting raped?

I don’t know if there is a certain behavior or attitude a woman can have to ward off potential rapists – that’s a whole different ballgame. I think it can happen and does to all kinds of women, confident or not. It’s dangerous to say, ‘If the woman had been more confident or did something different then she wouldn’t have been raped.’ It’s really more the rapist that we should be asking: what can be done to teach these men how to treat women (and people in general) with respect and not use your cock as a weapon? Rape isn’t sex – it’s a power trip and a pathetic one at that. I turn down many men, but I do it gently and respectfully.

What turns you on in somebody?

I’m not a cougar in the sense of going on the ‘prowl’ and looking for young men to buy things for or take care of. I’m actually quite the opposite. I like men of all ages and I am more about them taking care of me.

Is it all about making love or is there a love angle too…in that old-fashioned romantic sense?

I really only have one person I am in love with and it’s totally separate from the guys that I play and shoot with. It’s totally different and hard to explain. Not that I don’t care about these other men but it’s just for the time we are together. I play with a lot of people to be honest, I don’t even remember most after about a week. I know that may sound very slutty and possibly shallow. But if I recall each encounter or try to hold that memory in my head I think my head would explode. Just too many, really. Some have become friends for sure but not in the romantic sense.

How random are these hookups?

Besides this one true love of mine, the others are there for artistic reasons only, not that I don’t feel something in the moment for them but it’s not at all a love situation. The only requirement I have for photo play is a mutual respect, and it’s a paid situation, so a photo play client needs to have financial ability to pay – and of course be respectful. Open-minded is always a plus. In the case of the random hookups, it’s just pure chemistry and unique situation, and almost always instigated by me or it’s mutual. If a guy is the one pursuing it can be a turn off for me. Not that it’s not flattering but I lose interest. Best is when somehow we just connect, like the rug guy in Istanbul. Or the pilot I met in a bar that never experienced a strap-on, whom I took him up to my room and showed him my toys and one thing led to another.

You were a disillusioned corporate worker, overweight and distraught, before you decided to follow your dream. What was the makeover like?

I lost 75 pounds thanks to a programme called Jenny Craig, somewhat like Weight Watchers, with prepackaged food. But on top of that I worked out like crazy – just somehow got fixated and determined to lose the weight. I fell in love with my boss and it just made me want to jump back into life – to feel sexy and alive. I wanted to feel good and look good. And I had to do surgery afterwards, to remove excess skin after losing so much weight. Doing it so fast didn’t give time for my skin to bounce back. Everything sagged, so I had my boobs done – they look and feel extremely natural, as I had implants through the belly button, and a tummy tuck, the works. It was a rebirth, like I finally had the body that was meant to be me.

It’s a constant struggle for me to stay fit. I go from working out every day to taking months off. I don’t know why it’s such a difficult thing for me to stay on a regular routine. I am on top of it but sometimes better than other times. I am fasting this week, just drinking protein shakes and working out.

Looking good is important in your line of work.

It’s extremely important. I want to look how I feel – sexy. Not to mention the energy you have when you take care of yourself. A person’s sex drive also increases when you work out regularly. If I feel like I look good, I feel sexier. I think how you look is a reflection of how you feel about yourself.

Besides shooting raunchy fantasies, would you take up something tamer, say like a wedding ceremony? Or will you insist they throw in the nuptial night as well? Ha ha…

I joke about that too. I would be happy to do the honeymoon. I have only shot a wedding once, for a friend and hated every second of it. I do shoot quite a few musicians and music videos, however. And before I shot erotic I worked for a newspaper and magazine, shooting current events, sports, and real estate. The magazine was a sound-related publication that introduced me to the movie and music industry in LA. I think music is a lot like sex – it’s raw and soulful and revealing.

How important it is for you to immerse in – by being a participant – what you are filming?

I discovered pretty early on that I am not a voyeur. I would go to swinger parties and while sometimes the guy I was with was content on watching I was much more about participating. That’s why when I started shooting erotic photography I put myself in the photographs almost right away. I felt almost immediately that I wanted to tell a story or immerse myself in the eroticism – it was my own photo therapy maybe.

Your family, friends and relatives. And that one-and-only. Are they supportive of your work?

My family has been very supportive. I am appreciative and somewhat surprised, quite honestly. My dad and sister and her family are very religious but we just don’t really talk about it much. I visit them and they visit me and we are close and I know they are happy for me. My nephews are about the same age or older than some of the men I have been with, so it got a little weird when I last visited them about a year ago. I went to a party and all my nephews’ friends were hitting on me. My nephews were very protective of their ‘Aunt Liz.’ I also have two daughters, who are now 22 and 25. I wasn’t doing the erotic photography and play when they were young and living with me. They are very supportive as well. But there have been some difficult situations, like when one of my younger daughter’s boyfriends asked her to introduce him to me. My daughter responded by saying, ‘I’m not her agent,’ and then broke up with him. But overall they know I am doing what I am meant to be doing, and that’s the greatest lesson you can teach your kids.

The one I was most worried about was my ex-boss, the one I had the affair with, the one that motivated me to lose the weight. I’m very much in love with him and worried that it could potentially really hurt him. For sure it shocked him. We went through a rough patch around it. But it’s all good now. We have been together for 14 years. To be honest, even if I hadn’t had the support or approval of my family or friends it wouldn’t have stopped me. I would have been a little bummed, maybe, but I’m doing what I love, it’s a passion. I feel it’s my path, to say it’s a calling may sound a bit odd but I can’t imagine not living this life. This is who I genuinely am.

You have, what comes to my mind is how Thoreau put it, ‘sucked out the marrow of life’ for over a decade. What’s left?

I look forward to every day. I still love everything I do, and feel extremely lucky that I am in the place that I am in. I am not even close to feeling burnt out. I love new experiences, and meeting people. Maybe, just maybe, when I am 70 I will get married or live with someone and hope I’m still shooting. Even if I’m not in the shots.

A joke I just came up with: when the cougar travels everybody goes places. Do you like it?

Very funny.