What do you wear when you are soon going to doff it for a copulation session for canvas? What was that semaphore again for more shisha in the hookah? How long does one keep jigging for the frolicsome mood to be captured as still life? At the Qudsia Bagh in Civil Lines I tried to lay a handle on some possible existential crises of Mohammad Shah ‘Rangeela’ (‘The colourful’), one of whose begums built the eponymous garden. The crossdressing debauchee was also the longest serving Mughal emperor since Aurangzeb. Well, he lasted long – nearly three decades from 1719 to 1748 – largely because he busied himself with these more, well, immediate issues rather than the regular drawn-out ones like, say, war strategies and kingdom expansions. He also didn’t engross himself much with a popular pastime of the period which enjoyed regal patronage, an activity which led to the untimely – and mostly gory – demise of seven rulers in the 12 years before him – conspiratorial killing of blood relations posing any threat to your own ascension.

While plenty has been known, envied, and seen of Rangeela not much has been written about the Qudsia Bagh, garden, which could be because not much is left of it. A sprawling pleasure garden, this was at par with the famed Vauxhall along the Thames and laid out in 1748 typically along the banks of the Yamuna which later decided to course further east. Where the river once flowed is the Ring Road today. The English retribution following the uprising of 1857 saw to it that the stately ornate buildings and winding water pathways of the garden were rendered vengefully mouldered. Development and related encroachment in an independent India saw the garden wither to 50 and then 30 acres. Today local estimates place the area at a vastly diminished 20 which is expected to shrink further once the ongoing work on the Metro line next to it is complete. And with it turn away many birds, including rare migratory ones, which pass by.

As shrivelling green lungs vanishing verdure seem to be a matter of distant if not a concern soon receding-into-irrelevance for the city dwellers. This is going by the pollution levels which, during Diwali this year reached 17 times the prescribed danger limit. In a city where every third child has a respiratory condition there was little thoughtful cessation in the cracker-bursting revelries. The gasping situation has provoked no active curbs from the authorities and the condition is projected to get worse with the marriage season around the corner.

But what subsumed me at the moment was the wonderful and massive gateway unimaginatively called the ‘Haathi Darwaza.’ (Massive gateways all over India are called ‘Haathi Darwaza’; I shan’t be surprised if in all these cases it is ASI the unimaginative godfather.) Trying to make up for what the ASI lacked I imagined Qudsia Begum enter the garden sitting astride an elephant. Not very far-fetched by any yardstick. Quli Khan in his travelogue Muraqqa-i-Dihli (The Delhi Album) chronicling the Sufi saints and dance girls and rent boys of Delhi under Rangeela also mentions a Nur Bai who travelled only on elephants who ‘ruined many houses.’ (You should join the ASI if you think this destruction was brought on by trampling.)

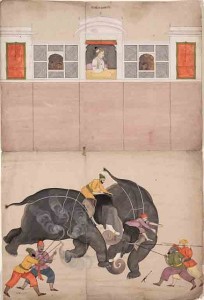

Qudsia Begum was originally Udham Bai. A gifted dancer, Udham Bai’s seductive moves charmed Rangeela who soon married her. Udham Bai thus became Qudsia Begum who went on to create one of the finest pleasure gardens in the world at the time probably replete with its own promenades, bandstands, fountains and maybe a harem even to ensure her husband visited often. It might have been difficult to hold on to a lotus-eating emperor whose pleasure-seeking pursuits covered the whole gamut from fetish to fear. Widely spotted in women’s clothes, he was rumoured to have been impotent – to counter which, it’s said, some of the paintings were commissioned. The most noteworthy that of him fornicating in near nudity, female attendants fanning draught and desire. Others include a celebration of Holi, watching an elephant fight from a safe height and another framed by a jharokha. This style of painting pioneered by Nidha Mal grew to be a rage among other rulers. Rangeela could have sucked on his hookah, straddled the courtesan or cut a rug for the paintings in the garden where I was strolling now.

By the side of the path leading to the gateway were the derelict ruins of a pillar with peeling stucco baring the ordered maze of fine Lahori brickwork beneath. Corbel remains pointed to a taller and probably more elaborate structure. Tousled with creepers, determined some clung to it concealing open wounds – preserving whatever of the grandeur left. Inside the Darwaza I was flanked by not dark, dingy sally ports, a fort staple, but stairways that wound all the way up to an airy, sunny terrace. It seemed to have been once sequestered from view by columns with florid motifs; what remained were baroque bases and bulbous stubs of tops awaiting further beheading by a passing gryphon. Hundreds of pigeons arose in a cooing flutter like they do ahead of the hero and heroine running in slomo holding hands with the Gateway or India Gate in the background. Some did a flying scat protest as I stepped into their cereal breakfast just served by the garden attendant.

Govind’s un-washed, oversized shirt fell like a soutane. A gormless but otherwise avuncular man, he carried the harried air of a single working mother on a PTA Saturday. He paused for my questions and itched out his answers from his balls.

‘The British built so many buildings all over Delhi. Nobody should expect me to remember their names.’ This was the gist of what he said before shuffling away now trying to positively pry his balls out. I walked away before he could lob them at me in case he succeeded.

Concrete walkways wound their way around the park and passed by benches where people sat mirthlessly guffawing their way into yogic longevity. If the Metro work didn’t scare away the birds, this would, I thought. Amorous youngsters, seemingly diddling to passers-by, dotted the lawns their hands disappearing into dupatta folds and jacket hems.

Rangeela was around.

Some more action: It is true that with the passing away of Syed Ausaf Ali, the revered historian last month, nobody knows Delhi anymore like the back of their hand. But it is only fair that those employed by the ASI, like Govind (surname and photograph withheld to protect sorry identity), should at least know the history of the site they are posted to. Govind, as I said in the post, did tell me the buildings in the Qudsia Bagh were built by the British whereas most of it were destroyed by them. True, I knew about the Qudsia Bagh more or less when I visited but I didn’t know about the Mohammad Shah connection. When Govind told me it was all built by the British I felt like crying; when he said nobody should expect him to remember names I felt like kicking the body part he was busy raking.

Some more action: It is true that with the passing away of Syed Ausaf Ali, the revered historian last month, nobody knows Delhi anymore like the back of their hand. But it is only fair that those employed by the ASI, like Govind (surname and photograph withheld to protect sorry identity), should at least know the history of the site they are posted to. Govind, as I said in the post, did tell me the buildings in the Qudsia Bagh were built by the British whereas most of it were destroyed by them. True, I knew about the Qudsia Bagh more or less when I visited but I didn’t know about the Mohammad Shah connection. When Govind told me it was all built by the British I felt like crying; when he said nobody should expect him to remember names I felt like kicking the body part he was busy raking.

On the rolls of a prestigious, responsible and well-funded body, it’s not too much to expect Govind to tell me the correct history of the garden and introduce me to Rangeela. If Govind is busy feeding pigeons or dismantling his own body parts, the ASI should at least put up a board with the history on it. I shall write to the ASI as well as mark a copy to the email provided in the signboard here. Progress shall be duly noted in the comments section below.